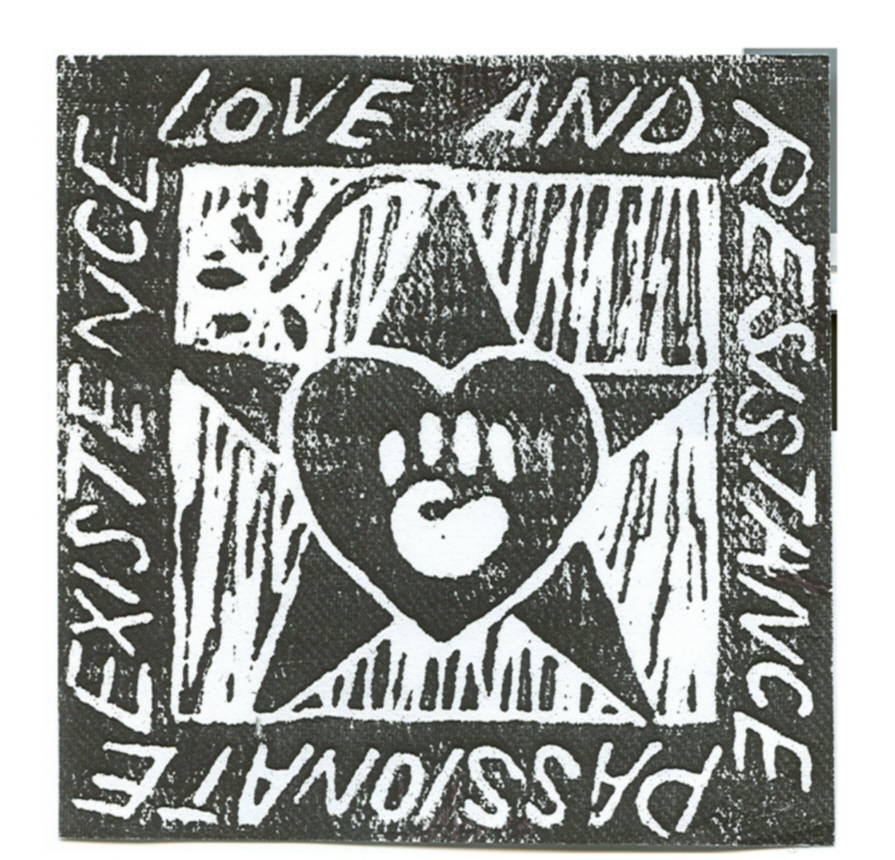

(this slightly shortened and edited article was originally printed in The Martlet, November 18, 2004, Victoria, BC) photo by T. W.

A day spent ‘dreaming on’ with Victoria’s silent protesters

Dressed in black, a group of about 15 predominately middle-aged and retired women stand in silence next to City Hall in downtown Victoria on a chilly Thursday afternoon. Along the sidewalk they hold banners. A black banner with white lettering says, “Women In Black— Creating a World Without War and Violence.” Another one says, “White Poppies for Peace.”

Creating a World Without War and Violence.” Another one says, “White Poppies for Peace.”

On the sidewalk a woman gives out white poppies and information notes to passersby. The notes explain that the white poppies are a symbol of active peace work and that this honours the war dead by seeking non-military solutions to war.

They are Women In Black (WIB), a loose worldwide network of women (and some men) that meet in public places and stand in silence. WIB vigils began in Israel in 1988 when women were protesting Israel’s occupation of the West Bank and Gaza. In Victoria, WIB has been holding silent vigils once a month for the last 10 years to protest issues related to violence and war.

It may be elusive, and its impact may be incalculable, but it is still being noticed. In fact, the movement was even nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize 2001. It’s no doubt unusual, but that seems to be working for the WIB and may even be why The New VI and Shaw’s the Daily showed up with camera in hand at City Hall on the day of the white poppy protest.

During each vigil the local contingent gives out information leaflets on a different issue, from Canadian government policy to mammoth-scale international injustices. Yearly, they commemorate the women murdered by a gunman in a Montreal classroom in December, 1989; in August the remember the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.. They have also opposed wars in Kosovo, Columbia, Palestine, Afghanistan and Iraq.

All around the world—in Vancouver, Brisbane, Jerusalem, Johannesburg, Amsterdam, Istanbul, Moscow, New York, Paris, London, Rome, to name just a few—WIB continues to stand in black at silent vigils.

The WIB traditions of wearing black and standing in silence are no coincidence. That much black apparel in one place makes me think of a funeral, a fitting association considering WIB mourns the injustices of the world at the silent vigils. Plus, if the banners weren’t enough, it sure makes the group stand out in a crowd.

As the black outfits distinguish the women from passersby, the tradition of silent protesting even distinguishes the WIB from other protest groups. “A typical protest is about getting one’s voice heard . . . and into some kind of public sphere,” said William Carroll, a University of Victoria sociology professor who researches social movements.

But because of WIB’s origins, anything but a silent protest was not feasible. In Israel and Palestine, women were harassed a great deal—silence was the only way to deal with the insults. It was practical then but continues to hold symbolic meaning today. “It represents being a witness of war, and represents possibility and hope,” said Terry Wolfwood, the group’s co-founder and one unofficial spokesperson.

On an overcast November day, I silently joined the group. As I approached cautiously, dressed in black from shoes to jacket, Wolfwood ushered me towards one end of the 12-foot-long black banner.

A day earlier, I met with Wolfwood, who told me of the sometimes-hostile reactions from passersby. “We don’t answer any hostility. We only give out information,” she said. However, I could still hardly believe that anybody could possibly heckle a bunch of women standing in silence for peace. Instead, I was thinking about Wolfwood’s explanation of the powerful feeling the women got as they made their cause visible and stood accountable. I wanted to feel it for myself.

Her explanation did not prepare me for the feeling I got as I stood there, in public, in silence, in black. At first I felt a little silly. But the silly feeling soon passed, and I grew spellbound by the mixed, and sometimes curious, reactions of passersby.

A few minutes into the protest, a disgruntled man got off the number 14 bus at the stop in front of our vigil. He took one look at us and said in a huff, “What do you guys think? Women aren’t capable of violence either?” Although I had been warned of these hostile responses, somehow it was difficult to understand how anyone could be so quick to judge. How could these women stand silent and just listen? I wanted to retaliate. But as a WIB, I knew that wasn’t possible.

Soon after, a middle-aged woman with a black scarf approached our group of women and said with a look of deep sorrow, “I have to agree with all of you. That’s why I’ve been weeping since Bush has come in.” Wolfwood, who was in the midst of giving out white poppies, replied, “Well, have a white poppy and have hope.” The woman in the black scarf took the poppy and stood with the group. She too became a WIB.

Taking a stand and being visible became contagious. For one afternoon people took notice and thought about peace in our society. The public vigil didn’t touch everyone, but you could tell that it truly moved some. There were honks. There were smiles. There were waves. There were also a few emphatic thumbs up.

I amazed myself by my inability to judge what people’s reactions would be, based on their appearance. From street people to businessmen to earthy, hippy types, their reactions varied as the much as the people themselves. When the sidewalk spokesperson, a white-haired woman wearing peace sign earrings, attempted to give a white poppy to a young woman in her early 20s, the young woman forcefully said, “Excuse me—don’t harass me, okay?”

But by that time I understood how these women could stand out there, with no expectations and no shame. They were empowered. They didn’t need to change the views of people who didn’t share their perspective on the world. The hostility was overshadowed by support.

In fact, Wolfwood said that sometimes heckling even motivates the WIB. She said that one day a woman walked by the vigil and loudly proclaimed. “Dream on, women. Dream on.” Unshaken, Wolfwood thought to herself that, yeah, she would dream on. “It’s important to me to have a dream. But then you have to express your dreams,” she said.

Although Carroll considers silence to be an unusual way to protest, WIB is not the only group using silence as a method to protest. Even members of the British Columbia Government Employees Union held silent protests last April.

According to Carroll, this is a credible alternative to lobbying politicians directly. The WIB, he said, is engaging in a form of cultural politics—they may be “trying to shift the way people think about issues rather than how we can influence in the here, in now.” He said when political groups orient themselves towards getting through to the people in power, they are limiting the scope of what can be done and what issues can be addressed. “If the problems are more deeply structured, it’s important to look at different aspects that can lead to social change,” he said. “Social movements generally develop as alternatives to conventional parliamentary politics.”

According to Wolfwood, not only did the tradition of silence originate in Israel, but so too did the tradition of the group being made up of women. “There are still taboos in some societies about men attacking women. Therefore, it’s more possible for women to do this and for police and soldiers not to attack them,” she said. “Militarism is a patriarchal value.”

Despite the movement’s Israeli origins, there are many reasons why women all over the world are on the forefront of any anti-war movement. CBC Newsworld reported that women are among the most vulnerable and the least heeded when it comes to making decisions about going to war— women who are systematically raped by male soldiers and women who shoulder the responsibility of keeping their families together while their fathers and sons are off fighting. Wolfwood also pointed out that the social instability resulting from war creates conditions that trap women in poverty and force many into homelessness and prostitution.

“The nature of war has really changed. Before World War II it was almost only soldiers that died,” Wolfwood said. “But now about 80 per cent of deaths are women and children—unarmed civilians.”

However, she admits there is some room for bending the traditions. “We don’t turn anyone away that supports us,” said Wolfwood. And men often do. During the November peace vigil, without speaking a word, a Middle Eastern man who was passing by joined the silent protest.

A quick Google search reveals oodles of WIB groups in cities worldwide, though there is no official umbrella organization linking their efforts.

This is part of the WIB philosophy. The New York based website www.womeninblack.net, which acts as a starting point and information centre for WIB, says, “Women in Black is not an organization, but a means of mobilization and a formula for action.”

In Victoria, the Barnard-Boecker Centre Foundation (BBCF) links WIB and other like-minded individuals. Wolfwood is also the director of the BBCF non-profit society, which aims to create, to develop and to encourage programs that promote social justice, peace, sustainability, diversity and community. It also organizes public events that contribute, globally and locally, to knowledge and awareness.

The local network also promotes the work of the University of Victoria’s Vancouver Island Public Interest Research Group, which opposes Canada’s co-operation with the United States on its missile defence program. Peace activists are concerned that the program will spark a new arms race, exacerbate tensions between nations and violate international peace treaties. WIB handed out leaflets on this issue at a recent silent vigil. Since surveys show about 70 per cent of Canadians are opposed, Wolfwood believes that “this one’s winnable.”

Another link that ties together these organizations with similar memberships and ideologies is a newspaper with a circulation of 2,500 called Our Paper which Wolfwood co-founded. The paper aims to produce an independent, progressive publication committed to social justice, peace and environmental protection, and it is available at the university’s Student Union Building.

While a wide variety of age groups are represented in this loose community of progressive voices, WIB is mostly made up of older women. “Older people have a lot of power in society because we don’t have to conform,” said Wolfwood.

Carroll says, “Older people . . . have a fair amount of discretionary time and economic resources. If they’re interested in politics, they have greater opportunities to engage.” He says that another reason may be that the older generation of political activists may have been active in social movements in the 1960s, when many would have been in their thirties.

The impact of the WIB movement is difficult to measure. However, Wolfwood and gang show no sign of slowing down. And why would they? “A lot of people in my position seem to lack meaning in their lives. Resistance, the presentation of another possible way, gives life meaning,” said Wolfwood. “When people come together for a purpose, they’re saying there is a possibility.”